Lolly Willowes: or, The Loving Huntsman by Sylvia Townsend Warner

When I check my Substack homepage, I am inevitably faced with a wall of Notes. Most of these are amusing, interesting or charmingly irrelevant; Bloomsbury paintings, photographs of sheep, thoughts on Anglo-Saxon word derivation, that sort of thing.

The other type will be familiar to everyone else on here - it’s the ‘I grew my Substack subscriptions to 40,000 people in one month, you can do the same in only eight hours a day!’ All you have to do is put in the work, be consistent, keep showing up, keep writing, keep creating, keep on and on and on. And if you crash and burn with exhaustion, it’s probably your own fault anyway for not doing your self-care right.

None of this is anything new. It’s the good old Protestant work ethic rearing its tiresome head again, in a new, improved, ‘let’s all be creative!’ format. You might think that you’ve escaped the dull corporate grind of the day in the office, but the all-conquering diktat of productivity manages to rear its head in many different guises. There seems to be a pervading belief in some quarters that your worth, your usefulness to society, lies in what you do, not who you are. After all, if you’re not doing, not producing, not carpe’ing the diem, are you even alive?

But what started me thinking about all this? My recent discovery of Lolly Willowes, by Sylvia Townsend Warner. Someone on Substack (alas, I can’t remember who) mentioned in a note that ‘everyone’ was reading it, and I happily jumped on the bandwagon. I was planning a post on books about middle-aged women who dramatically change their lives (is that a genre? If not, it should be) and I thought this might fit the bill.

Before I read it, my sole knowledge of the book was that the main character moved to the country at some point. I had no idea what happened afterwards - I presumed she would make friends with the locals, take up gardening, maybe have some sort of Molly Clavering-style gentle romance with her next-door neighbour.

Reader, was I wrong.

But before we dive in for a closer look, let’s just take a minute to say something about the author. Sylvia Townsend Warner was a woman of many facets - born in 1893, she was a lesbian, committed Communist, musician and musicologist, as well as writing novels, verse, and short stories (many of which were published in the New Yorker). Lolly Willowes was her first novel, written when she was 33 (preceded by a volume of poetry), and the book’s enthusiastic reception encouraged her to take up writing as a full-time occupation.

Lolly Willowes is a curious book; satirical, humorous, sad and polemical, it was taken by many of its contemporary readers as a charmingly whimsical fantasy, which Warner was less than thrilled about. As she wrote to a friend, ‘I felt as though I had tried to make a sword, only to be told what a pretty pattern there was on the blade’.1 We first meet Laura Willowes (‘Lolly’) as she goes to live with her brother and sister-in-law following the death of her father, ‘as if she were a piece of family property forgotten in the will’. Laura is a sympathetic character though not a dynamic one - she is not a woman who is determined to seize her fate:

Her upbringing had only furthered a temperamental indifference to the need of getting married—or, indeed, of doing anything positive…

It is in this same passive spirit that she accepts the move to London and her brother’s household, ‘ready to be disposed of as they should think best’, leaving her childhood home for good. The perfect set-up for a fairytale heroine, you might think. But Laura is no Cinderella, and Warner is too subtle a writer to transform her into a mere household drudge. And so at the beginning her usefulness is merely make-work, a way of fitting in with the general business of the whole family:

Indeed, it was surprising how much there was to do, and for everybody in the house… Caroline never sat with idle hands; she would knit, or darn, or do useful needlework. Laura could not sit opposite her and do nothing. There was no useful needlework for her to do, Caroline did it all, so Laura was driven to embroidery. Each time that a strand of silk rasped against her fingers she shuddered inwardly…

This is a house where there is an unspoken expectation that one must keep busy, keep producing, even if what you are doing or producing is not, in fact, of any use whatsoever. Laura colludes in this belief, gradually moving away from her ‘real’ self to become the useful ‘Aunt Lolly… indispensable for Christmas Eve and birthday celebrations’. But the more necessary she becomes to the family, the more her agency and her own personality are eroded; her willingness to accede to the family - and society’s - expectations of her as a single woman has trapped her in her role as the helpful spinster aunt.

She found that after all she had done few of the things she intended to do. She would have liked to go by herself for long walks inland and find strange herbs, but she was too useful to be allowed to stray…

Even the advent of war fails to shake things up; she is allocated a job packing parcels to send out to the front, a job which she is so good at (making herself useful again) that she continues there for the full four years and is never given anything else to do. By this point in the book, if you are anything like me, you will be desperate for Laura to assert herself for once and escape the oppressive tedium of her life. But apart from the repressed feelings that express themselves in anxiety and extravagant flower purchases every autumn, she seems to be curiously unaware of her situation.

And then suddenly, after a chance encounter in a grocers’ shop, something shifts. Responding to her recurring vision of being ‘in the country, at dusk, and alone, and strangely at peace’, Laura buys a guidebook of the Chilterns and starts planning her flight. This is perhaps an echo of an episode in Warner’s own life when in 1922, while visiting Whiteley’s bookshop, her attention was caught by a map of Essex (a place she had never visited). Delighted by ‘the blue creeks, the wide expanses of green for marsh, the extraordinary Essex place names’2, she subsequently visited the area more than once and it became a place of special significance for her. Much in the same way, Laura pores over her guidebook of the Chilterns, eventually deciding that the village of Great Mop should be her new home.

Initially revelling in her freedom, she is shaken in her belief that ‘nothing could ever again disturb her peace’ after her nephew Titus decides to come and live in the village. Laura feels that she is being forced back into her old life:

In vain she had tried to escape, transient and delusive had been her ecstasies of relief. She had thrown away twenty years of her life like a handful of old rags, but the wind had blown them back again, and dressed her in the old uniform… she was the same old Aunt Lolly, so useful and obliging and negligible.

Below this picture are SPOILERS for the rest of the story. If you’d like it to remain a surprise, stop here! You can download Lolly Willowes from Project Gutenberg for free here or scroll right down to the bottom of this post to read an extract from the book.

But this time Laura is determined to resist, ‘I won’t go back. I won’t.... Oh! Is there no help?’ And she is answered by none other than the Devil himself; the ‘Loving Huntsman’ of the book’s title. When she returns home she is greeted by a kitten; her new familiar now that she has become a witch.

The reader is thus abruptly jolted away from the stolid sense of normality that has pervaded most of the book so far, and plunged into a strange new world; Laura drives Titus away with plagues of flies and mice, sours the milk, and attends a witches’ Sabbath (which bores her). But this is not just an enjoyable fantasy. Warner is making the point that becoming a witch is the only way in which women like Laura can gain their freedom and break away from society’s obligations.

Novels about spinsters bucking expectations and forging a different path were nothing new during this period - think of Muriel in The Crowded Street, turning down marriage in order to follow her own ideas of service - but where this differs from other books, to me, is that Laura is not attempting to pursue some alternative achievement, such as a career. Rather, she is fighting for the right not to do anything in particular - just to think, to walk, to dream, to live for herself rather than being helpful to others. In an environment that demands of women that they are either marriageable or useful, this is a radical suggestion. Warner is insisting on the rights of women to exist simply for who they are, not for what they can produce.

In her passionate outpouring to the Devil at the end of the book, Laura explains her point of view more clearly -

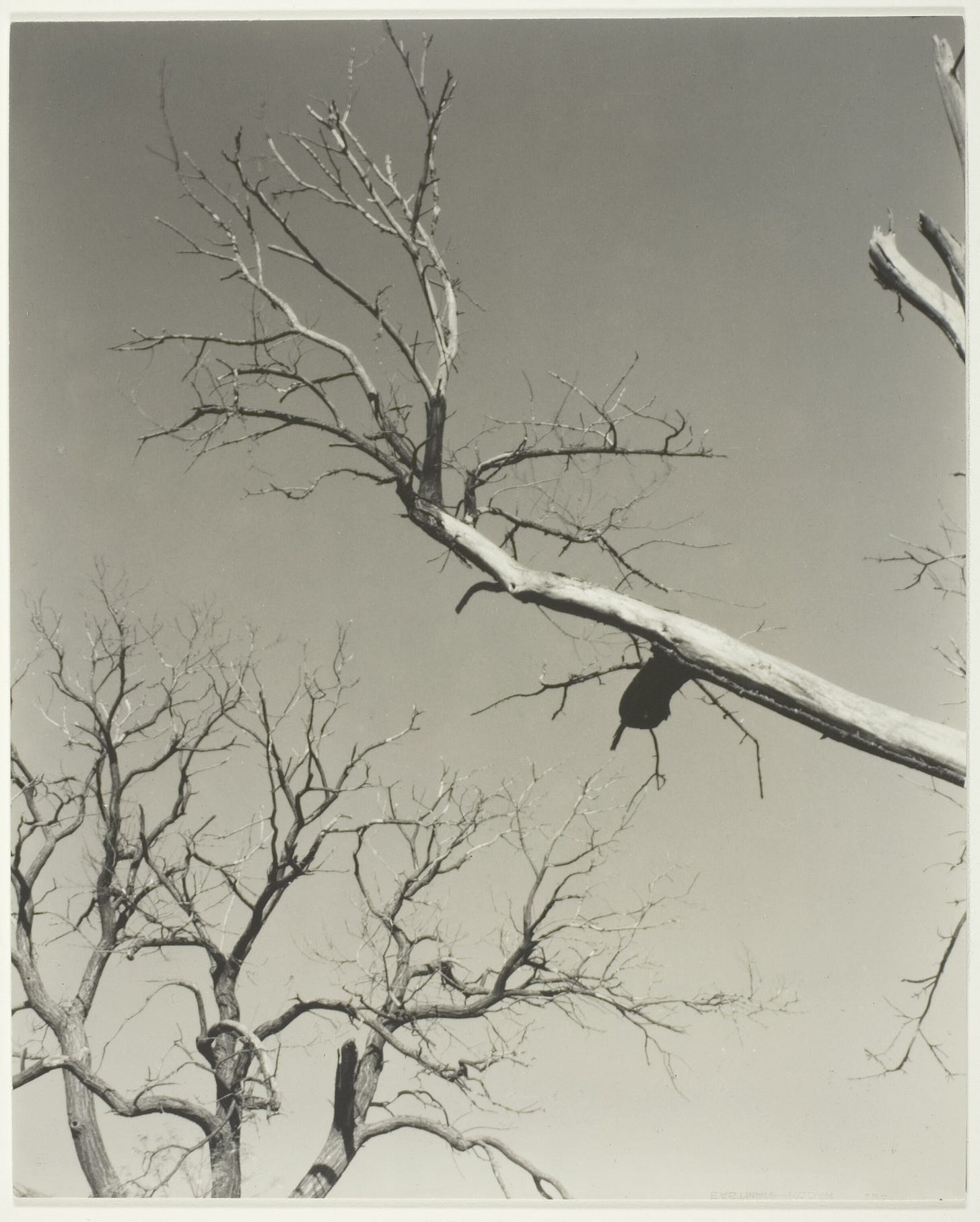

‘When I think of witches, I seem to see all over England, all over Europe, women living and growing old, as common as blackberries, and as unregarded… If they could be passive and unnoticed, it wouldn’t matter. But they must be active, and still not noticed. Doing, doing, doing, till mere habit scolds at them like a housewife, and rouses them up—when they might sit in their doorways and think—to be doing still!’

A lot has changed in the hundred-odd years since Sylvia Townsend Warner wrote this novel. Women can live alone, aunts aren’t expected to dedicate themselves to their nieces and nephews, and I’m pretty sure no-one ever feels obliged to do embroidery. But when it comes to keeping busy, ‘doing, doing, doing’, it feels like some things never change. In this way, perhaps sadly, Lolly Willowes is as relevant - and as revolutionary - as it ever was.

So next time one of those Notes pops up and you start feeling pressured and guilty - don’t. Take a walk, pick some herbs, go to sleep in a pile of leaves.

Black hat and broomstick optional.

Extract

In this section, which comes towards the middle of the book, Laura breaks the news of her move to the countryside to her family:

‘When I have evicted my tenants and brewed a large butt of family ale, I shall invite you all down to Lady Place,’ said Titus.

‘But before then,’ said Laura, speaking rather fast, ‘I hope you will all come to visit me at Great Mop.’

Every one turned to stare at her in bewilderment.

‘Of course, it won’t be as comfortable as Lady Place. And I don’t suppose there will be room for more than one of you at a time. But I’m sure you’ll think it delightful.’

‘I don’t understand,’ said Caroline. ‘What is this place, Lolly?’

‘Great Mop. It’s not really Great. It’s in the Chilterns.’

‘But why should we go there?’

‘To visit me. I’m going to live there.’

‘Live there? My dear Lolly!’

‘Live there, Aunt Lolly?’

‘This is very sudden. Is there really a place called ...?’

‘Lolly, you are mystifying us.’

They all spoke at once, but Henry spoke loudest, so Laura replied to him.

‘No, Henry, I’m not mystifying you. Great Mop is a village in the Chilterns, and I am going to live there, and perhaps keep a donkey. And you must all come on visits.’

‘I’ve never even heard of the place!’ said Henry conclusively.

‘But you’ll love it. “A secluded hamlet in the heart of the Chilterns, Great Mop is situated twelve miles from Wickendon in a hilly district with many beech-woods. The parish church has a fine Norman tower and a squint. The population is 227.” And quite close by on a hill there is a ruined windmill, and the nearest railway station is twelve miles off, and there is a farm called Scramble Through the Hedge....’

Henry thought it time to interrupt. ‘I suppose you don’t expect us to believe all this.’

‘I know. It does seem almost too good to be true. But it is. I’ve read it in a guide-book, and seen it on a map.’

‘Well, all I can say is....’

‘Henry! Henry!’ said Caroline warningly. Henry did not say it. He threw the cushion out of his chair, glared at Laura, and turned away his head.

For some time Titus’s attempts at speech had hovered above the tumult, like one holy appeasing dove loosed after the other. The last dove was luckier. It settled on Laura.

‘How nice of you to have a donkey. Will it be a grey donkey, like Madam?’

‘Do you remember dear Madam, then?’

‘Of course I remember dear Madam. I can remember everything that happened to me when I was four. I rode in one pannier, and you, Marion, rode in the other. And we went to have tea in Potts’s Dingle.’

‘With sponge cakes and raspberry jam, do you remember?’

‘Yes. And milk surging in a whisky bottle. Will you have thatch or slate, Aunt Lolly? Slate is very practical.’

‘Thatch is more motherly. Anyhow, I shall have a pump.’

‘Will it be an indoor or an outdoor pump? I ask, for I hope to pump on it quite often.’

‘You will come to stay with me, won’t you, Titus?’

Laura was a little cast-down. It did not look, just then, as if any one else wanted to come and stay with her at Great Mop. But Titus was as sympathetic as she had hoped. They spent the rest of the evening telling each other how she would live. By half-past ten their conjectures had become so fantastic that the rest of the family thought the whole scheme was nothing more than one of Lolly’s odd jokes that nobody was ever amused by. Henry took heart. He rallied Laura, supposing that when she lived at Great Mop she would start hunting for catnip again, and become the village witch.

‘How lovely!’ said Laura.

Henry was satisfied. Obviously Laura could not be in earnest.

When the guests had gone, and Henry had bolted and chained the door, and put out the hall light, Laura hung about a little, thinking that he or Caroline might wish to ask her more. But they asked nothing and went upstairs to bed. Soon after, Laura followed them. As she passed their bedroom door she heard their voices within, the comfortable fragmentary talk of a husband and wife with complete confidence in each other and nothing particular to say.

Laura decided to tackle Henry on the morrow. She observed him during breakfast and saw with satisfaction that he seemed to be in a particularly benign mood. He had drunk three cups of coffee, and said ‘Ah! poor fellow!’ when a wandering cornet-player began to play on the pavement opposite. Laura took heart from these good omens, and, breakfast being over, and her brother and the Times retired to the study, she followed them thither.

‘Henry,’ she said. ‘I have come for a talk with you.’

Henry looked up. ‘Talk away, Lolly,’ he said, and smiled at her.

‘A business talk,’ she continued.

Henry folded the Times and laid it aside. He also (if the expression may be allowed) folded and laid aside his smile.

‘Now, Lolly, what is it?’

His voice was kind, but business-like. Laura took a deep breath, twisted the garnet ring round her little finger, and began.

‘It has just occurred to me, Henry, that I am forty-seven.’

She paused.

‘Go on!’ said Henry.

‘And that both the girls are married. I don’t mean that that has just occurred to me too, but it’s part of it. You know, really I’m not much use to you now.’

‘My dear Lolly!’ remonstrated her brother. ‘You are extremely useful. Besides, I have never considered our relationship in that light.’

‘So I have been thinking. And I have decided that I should like to go and live at Great Mop. You know, that place I was talking about last night.’

Henry was silent. His face was completely blank. Should she recall Great Mop to him by once more repeating the description out of the guide-book?

‘In the Chilterns,’ she murmured. ‘Pop. 227.’

You can download Lolly Willowes from Project Gutenberg here.

If you enjoyed this piece, please comment! I reply to every one.

Quoted in the foreword to the Penguin Modern Classics edition, 2020

‘The Essex Marshes’, in With the Hunted: Selected Writings of Sylvia Townsend Warner, ed. Peter Tolhurst

Loved this Harriet! So interesting to focus on the aspect of ‘busyness’. Thanks for spoiler alert and the long extract at the end is a great idea. Hoping to finish my essay on Lolly today if my own chores don’t intrude!

Thank you Harriet for another engaging post. I came across this fascinating writer (for the second time) quite recently. After I’d finished Lolly Willowes, I went in search of more Sylvia Townsend Warner. I found her biography of T H White on my own bookshelves (read it years ago - too callow to recognise excellent prose when I saw it), then her diaries were dramatised on BBC Sounds. The more I found out, the more I wanted to discover. So glad that you and others are just as enthusiastic - and, more importantly, are spreading the word.