Eletelephony

Once there was an elephant,

Who tried to use the telephant—

No! No! I mean an elephone

Who tried to use the telephone—

(Dear me! I am not certain quite

That even now I’ve got it right.)

Howe’er it was, he got his trunk

Entangled in the telephunk;

The more he tried to get it free,

The louder buzzed the telephee—

(I fear I’d better drop the song

Of elephop and telephong!)

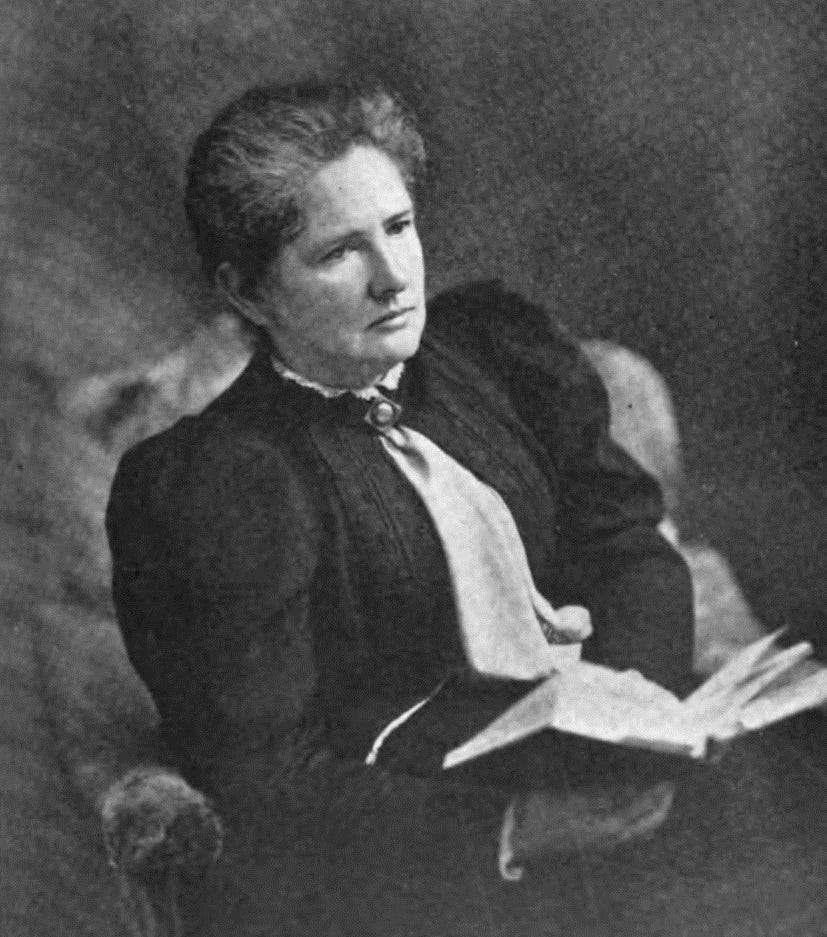

This delightful poem is perhaps the best-known by Laura Elizabeth Howe Richards - nonsense verse writer, Pulitzer-winning biographer, philanthropist and social campaigner. Richards is somewhat neglected today but she wrote over ninety books for children over the sixty years of her career, as well as several books for adults.

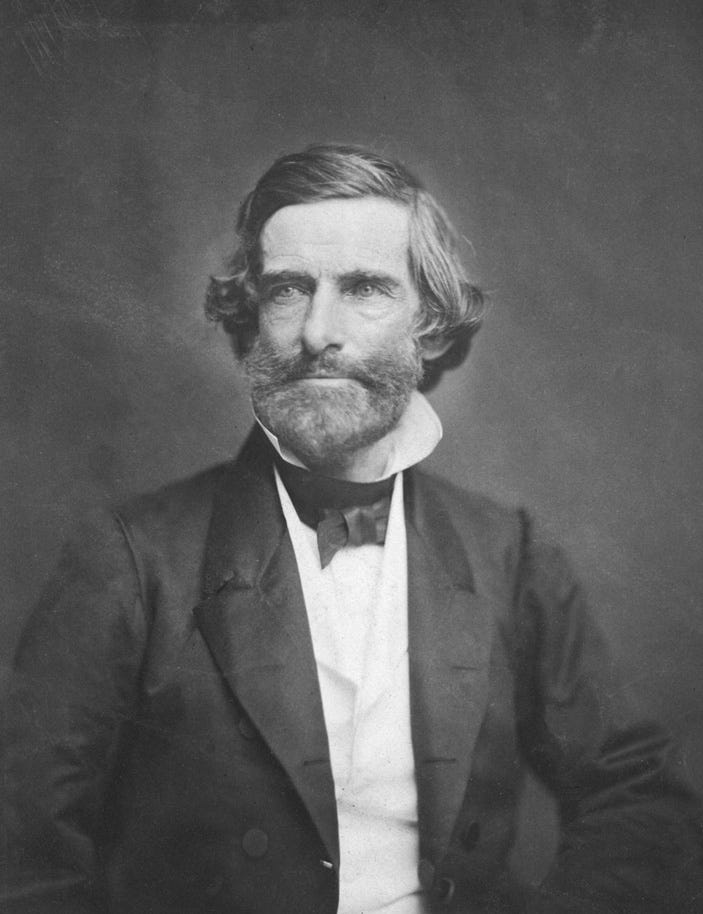

I can’t write about Richards without at least a mention of her remarkable parents, who she described in her autobiography Stepping Westward (1931) as ‘the two busiest people in the world’. Her father, Samuel Gridley Howe, is usually described as a philanthropist, which seems too tame a word to adequately describe this firebrand abolitionist and campaigner, who at the age of 23 went straight from Harvard Medical School to serve as a commander and surgeon for the Greeks in their War of Independence. Sharing the privations of the soldiers, he afterwards reminisced:

‘I have been months without eating other flesh than mountain snails, or roasted wasps… roasted to a crisp, and strung on a straw like dried cherries, they were not at all bad.’1

Howe later founded the Perkins Institute for the Blind, with his star pupil (and Richards’ namesake) being the deaf-blind Laura Bridgman, dubbed ‘the most famous girl in the world’ after being mentioned by Dickens in his American Notes.

Richards’ mother, Julia Ward Howe, was a musician and writer who spoke at least seven languages. Although she is most famous for writing to the words to the ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic’, she also published plays and volumes of poetry, as well as being an active campaigner for women’s suffrage. She and Samuel had seven children, and the family grew up in an intellectual atmosphere, with their parents’ acquaintances and correspondents including John Greenleaf Whittier, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Dickens, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Amos Bronson Alcott (father to Louisa) and Florence Nightingale (godmother and namesake to Laura’s sister Florence.)

With such a background, it is no surprise that all four surviving sisters became published writers. Laura herself did not start writing until after she had children, thanks to the the ‘weeks and months of quiet’2 that followed their arrival (something unknown to modern parents, I think!) She describes in her autobiography how she began by writing little songs and verses, not only for but on her children:

‘The first baby was plump and placid, with a broad, smooth back which made an excellent writing desk. She lay on her front, across my lap; I wrote on her back, the writing pad quite as steady as the writing of jingles required.’3

More books followed; nonsense rhymes, children’s fiction, an autobiography and several adult biographies, including of her mother (written with her sisters Maud and Florence), which won the first Pulitzer Prize for Biography.4 Her best-selling book was probably Captain January, later made into a Shirley Temple film, but her longer novels for girls were also very popular at the time, including my favourites - the Hildegarde/Three Margarets series.

The dates the Hildegarde books were published fall almost exactly between the Little Women books and Anne of Green Gables, and I think these are also the closest comparisons to the Hildegarde books themselves. There is a similar domestic mileu, and they all start off as fairly straightforward children’s books which evolve into more complex stories as their characters mature and enter into adult life. They share (in my opinion) a similar quality of writing; an opinion also voiced by the Manchester Guardian in this review from 1891.

There is much of Louisa Alcott's charm in Laura E. Richards's books… and the descriptions of American woodland scenery are more delightful and poetical than Miss Alcott's.

Queen Hildegarde follows our eponymous heroine, a pampered city girl who is sent, much to her displeasure, to spend her summer on a farm in the New England countryside. But her outlook is changed through her friendship and championing of farm boy Bubble Chirk and his invalid sister Pink, and the homespun wisdom of Farmer Hartley and his wife Dame Lucy. There’s also a hint of mystery thanks to a slightly improbable side plot about some long-lost family jewels.

This book is followed by Hildegarde’s Holiday, in which she and a friend spend the summer in the countryside with her elderly Cousin Plenty; Hildegarde’s Home, in which the family must adapt to a new life after a change of fortune; and Hildegarde’s Neighbours, which introduces my favourite characters, the Merryweather family. With their love of singing, literature and making up nonsense rhymes, it is very tempting to read into the Merryweathers some reflection of Richards’ own family life, with their charmingly eccentric, bookish mother perhaps a portrait of Laura herself:

Mrs. Merryweather sat in a low chair, with her lap full of books, and had some difficulty in rising to receive her visitors. Her hearty welcome assured them that they had not come a day too soon, as Mrs. Grahame feared.

"My dear lady, no! I am charmed to see you. Bell has had such pleasure in making friends with your daughter. Miss Grahame, I am delighted to see you!" and Mrs. Merryweather held out what she thought was her hand, but Hildegarde shook instead a small morocco volume, and was well content when she saw that it was the "Golden Treasury."

The last of these books is Hildegarde’s Harvest, which could be subtitled ‘Hilda Grows Up’, after which we move onto new characters in Three Margarets. This is ostensibly the start of a different series, which introduces three cousins - quiet, ladylike Margaret, fiery Cuban Rita, and ranch girl Peggy - as they spend the summer together in their uncle’s house. When it comes to reading order, this book and the next, Margaret Montfort, can be read at any time - but in the following book, Peggy, we bump into old friend Gertrude Merryweather, and this is where the two series collide. The events in Peggy take place after Hildegarde’s Harvest so make sure you’ve read all those books first, if you don’t want spoilers! The last three books are Rita (set during the Spanish-American War), Fernley House, and lastly (my favourite of the lot) The Merryweathers, in which, as Richards herself put it, ‘the various characters of the two series were brought together, paired off, and duly married.’5

This last book is set against the picturesque setting of a camp in the forest, based on the Richards family’s own summer camping ground at Lake Cobbosseecontee; the family later opened up a camp for boys in Maine, named ‘Camp Merryweather’, which ran for 37 years and included Teddy Roosevelt’s sons among its alumni (for more on the peculiarly American tradition of the summer camp, have a read of this).

Richards continued to write for many years, publishing her last book, What Shall the Children Read, at the age of 89. You can download many of her books (including the Hildegarde/Three Margarets series) for free from Project Gutenberg here.

Would you like me to write more about Laura E. Richards, Camp Merryweather, or novels featuring summer camps? Let me know!

I will leave you with an extract from Queen Hildegarde:

Well, my dearest Queen, here am I running on about myself, as if I were not actually expiring to hear about you. What my feelings were when I called at your house on that fatal Tuesday and was told that you had gone to spend the summer on a farm in the depths of the country, passes my power to tell. I could not ask your mother many questions, for you know I am always a little bit afraid of her, though she is perfectly lovely to me! She was very quiet and sweet, as usual, and spoke as if it were the most natural thing in the world for a brilliant society girl (for that is what you are, Hilda, even though you are only a school-girl; and you never can be anything else!) to spend her summer in a wretched farm-house, among pigs and cows and dreadful ignorant people. Of course, Hilda dearest, you know that my admiration for your mother is simply immense, and that I would not for worlds say one syllable against her judgment and that of your military angel of a father; but I must say it seemed to me more than strange. I assure you I hardly closed my eyes for several nights, thinking of the misery you must be undergoing; for I know you, Hildegarde! and the thought of my proud, fastidious, high-bred Queen being condemned to associate with clowns and laborers was really more than I could bear. Do write to me, darling, and tell me how you are enduring it. You were always so sensitive; why, I can see your lip curl now, when any of the girls did anything that was not tout à fait comme il faut! and the air with which you used to say, "The little things, my dear, are the only things!" How true it is! I feel it more and more every day. So do write at once, and let me know all about your dear self. I picture you to myself sometimes, pale and thin, with the "white disdain" that some poet or other speaks of, in your face, but enduring all the horrors that you must be subjected to with your own dignity. Dearest Hilda, you are indeed a heroine!

Always, darling,

Your own deeply devoted and sympathizing

Madge.Hildegarde looked up after reading this letter, and, curiously enough, her eyes fell directly on a little mirror which hung on the wall opposite. In it she saw a rosy, laughing face, which smiled back mischievously at her. There were dimples in the cheeks, and the gray eyes were fairly dancing with life and joyousness. Where was the "white disdain," the dignity, the pallor and emaciation? Could this be Madge's Queen Hildegarde? Or rather, thought the girl, with a sudden revulsion of feeling, could this Hildegarde ever have been the other? The form of "the minx," long since dissociated from her thoughts and life, seemed to rise, like Banquo's ghost, and stare at her with cold, disdainful eyes and supercilious curl of the lip. Oh dear! how dreadful it was to have been so odious!

Letters and Journals of Samuel Gridley Howe (1909) ed. Laura E. Richards

Stepping Westward (1931), Laura E. Richards

Ibid.

Julia Ward Howe 1819-1910, by Laura E. Richards and Maud Howe Elliott, ass. by Florence Howe Hall (1915)

Stepping Westward

I completely loved this piece, Harriet! The Eletelephony poem is a favorite with my kids, but that's all I knew from the author. The description of her parents is fantastic. I knew of the Iowa College for the Blind only through Laura Ingalls Wilder since her sister Mary attended it. I love that there's another literary connection to it.

Also, the part about the quiet weeks and months after a baby is born felt resonant. Any writing I've gotten done in the past year has been while I've been nap-trapped under my baby. The image of the baby's back as a writing desk is just wonderful. You hear about the 'pram in the hallway' or 'the baby on the fire escape' but I much prefer this image of harmonizing children and the creative life.

I'd love more about summer camp books! I read Poppies for England by Noel Streatfeild a few summers ago and had a lot of fun reading more about seaside summer family camps in England.

Just when you think you've heard of all the books... I will have to look up some of these - if not for myself, for a particular daughter who really loves Louisa May Alcott's writing. Thank you for sharing about these! (I do hope I'll be able to find some in print.)